Connecting to Memorial Day

From the Desk of Chuck Fuller

I imagine Memorial Day means something different to each of us, based on our connections to particular wars or branches or bases.

I grew up the youngest of three children, and the only boy. I wouldn’t learn until years after my father’s death that he shared stories about his World War II service with nobody else but me. My relationship with Memorial Day, then, centers on World War II, and on the Army Air Forces in particular.

What follows are three real stories about the World War II experiences of men with connections to North Carolina.

***

Wilbur Bazemore

Note: Ages and dates are approximate.

Hemingway, SC, forty miles west of Myrtle Beach, came into existence in 1911 as a small cotton trading community at the intersection of a new rail line. Some 15 years later Wilbur Bazemore was born, adding one more to the town’s 350-person population.

In the mid-1930s, ten years after Wilbur’s birth, a young girl named Elsie McDaniel arrived in Hemingway after her father, a sharecropper, purchased a farm there. In a town that small, Elsie and Wilbur surely knew one another throughout adolescence.

Late in the summer of 1944, as the Allies battled their way across Europe and Wilbur came of age, his number was called. Basic training lasted only eight weeks because of the dire need for infantry replacements. At the end of training, the Army afforded soldiers a few days to spend with their families before deployment. It was then that Wilbur and Elsie married.

As daily newsreels recounted the brutal Allied advance across the European continent, Wilbur and Elsie climbed into a car for the 80-mile drive from Hemingway to Charleston, where Wilbur would board a transport vessel and cross the Atlantic. The newlyweds cried the entire way.

Wilbur and his unit landed in Allied-controlled territory and made their way to the front line. By that time – winter 1944-45 – the Germans had launched a massive counteroffensive through the heavily forested Ardennes region, hoping to encircle Allied armies and force favorable peace terms.

The Battle of the Bulge claimed 19,000 American lives. Wilbur’s first day of combat was the last day he lived. Private Wilbur Bazemore, KIA, January 15, 1945. Survived by Elsie McDaniel, widowed.

***

Max Franklin Fuller

Elsie McDaniel, my mother, added “Fuller” to her name after she married Max, my father. They met in Charleston, SC, where they both worked at the Greyhound bus station, Elsie as an operator and Max as a ticket agent. We all moved to Raleigh in 1958 when I was six months old.

Fourteen years earlier, from April to August 1944, Max stood behind a 50-caliber machine gun pointing out an open window in the rear of a B-24 Liberator as it took off 50 times over 110 days. His squadron flew from airfields in Italy and Tunisia to bomb industrial targets all over occupied Europe. Flak and fighter plane attacks punctuated each mission.

My father, like every other airman, had to contemplate before every mission whether his plane would be shot down, whether he’d have time to bail out, whether the parachute would open, whether flak or a fighter would kill him. Over one stretch in July 1944, he flew six missions on six consecutive days.

On two of his 50 missions, his pilot had to crash land. One was back at base when the landing gear didn’t deploy because of damage sustained during the mission. But the other was in France, behind enemy lines. He and his surviving crew referenced a folding silk map, provided to every airman for just such an event, to navigate their way back to base.

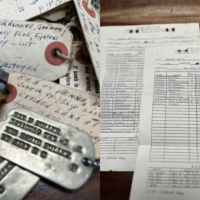

Max kept detailed records, even saving bomb fuse pins from every mission and adding notes about what happened. One that I have reads, “Raid on Bleckhammer, Germany. Rough heavy flak, fighters. Ship shot up – lost 5 planes. Target destroyed.”

My father completed his final mission – a raid on the oil fields in Ploesti, Romania – on August 18, 1944, five months before Wilbur died at the Battle of the Bulge.

***

John D. Lewis

Just outside of Sagan, Poland, razor wire encircled a 60-acre rectangle in which dozens of thin wooden 10’ x 12’ structures stood, each raised 24 inches off the ground to make tunnelling easier to spot. Within each structure lived 15 American and British airmen, captured after bailing from downed airplanes.

Inside one of these cramped quarters on December 6, 1943, twenty-five North Carolinians put ink on a blank page pieced together from empty Camel cigarette packs.

“We, the undersigned, having formed a club pursuant to the laws of the State of North Carolina and the occupied territory of Stalag Luft III, do hereby make, subscribe, acknowledge and file this charter as legal proof…”

What followed was a formal contract committing each signatory to supporting one another in bettering themselves and North Carolina upon their return home. None knew whether they would live to see the next day, but they endeavored to plan for their return nonetheless.

John Dortch Lewis, of Goldsboro, was named president of the club. Lewis came to the POW camp after his fighter plane was shot down over Tunisia. He evaded capture for a week by donning Arab garb and rubbing dark clay over his skin. He began planning his escape as soon as he arrived at Stalag Luft III.

Lewis tried and failed three times. Per the New York Times, “After one of Mr. Lewis’ escapes, he was brought back to face the German commandant, who asked him to give his word that he would not try to escape again. If he promised that, the commandant said, after the war he would make Mr. Lewis the police commissioner of New York. Mr. Lewis replied that he could not give such assurances and that, in any case, he was planning on becoming the Mayor of Berlin. He was sent to the isolation cells and put on a diet of bread and water.”

Lewis was true to word, and his fourth escape attempt succeeded. He slipped away from a prisoner work party in Munich and found his way to the advancing Allied lines.

After the war ended, Lewis returned to North Carolina, along with many of the other contract signatories. He, like the others, built a business, raised a family, and spoke little of his military service. Lewis played a prominent role in reactivating Seymour-Johnson Air Force Base in the 1950s.

He grew close to Gene Price, the former editor of the Goldsboro News-Argus, and agreed to speak publicly after a local screening of the 1963 film “The Great Escape.” After all, Steve McQueen’s character was based on him.

When asked after the screening what was in his mind when he kept trying to escape, Lewis replied, “I knew from the start that it would be a long war and that I probably wouldn’t come out of it alive, so I just wanted to run up the best score that I could.”

After the war, John returned to North Carolina and married Carolyn. They were married for 53 years and raised three children.

John D. Lewis died in 1999. After his death, his son found the contract, still intact and safely tucked into a tube among his father’s other wartime items.

***

Some men who went to war had big family networks back home. Some were already husbands and fathers with families of their own. Those are the ones we remember because they had someone to remember them.

But many, like Wilbur, were lost to history the day they died, before they could build a life and legacy. I’d be surprised if anybody has mentioned his name more than a few times in the past 50 years. There’s nothing wrong or right about that – it’s the reality of a horror that claimed 3% of the world population.

Memorial Day is about honoring the memories of John Lewis, Max Fuller, and Wilbur Bazemore, whose bravery and endurance all those years ago helped build the world we enjoy today.

Recent Articles

When Prayers are Heard, Answers Come: Finding Peace in Times of Crisis

From the Desk of Chuck Fuller “Our prayers, sir, were heard, and they were graciously answered” Many years ago, I led a task force responding to a series of tornados that devastated parts of eastern North Carolina. In our early discussions, we debated how many people needed to be impacted for us to implement a…

Read MorePassenger rail’s future in North Carolina

Thank you for joining us this Saturday morning. America once led the world in train travel. Routes spanned the continent and most people had easy access to a train station. But trains gave way to cars and planes, and by the 1960s privately owned train companies were bleeding revenue. In 1970, Congress passed and President Richard Nixon…

Read MoreThe Golden LEAF Foundation and North Carolina

Thank you for joining us this Saturday morning. Today we’re diving into one of the most impactful North Carolina organizations of the past 25 years: Goldean LEAF (“LEAF” stands for long-term economic advancement foundation)The nonprofit has largely flown under the radar for the past decade. That lack of public attention or controversy should be seen…

Read More